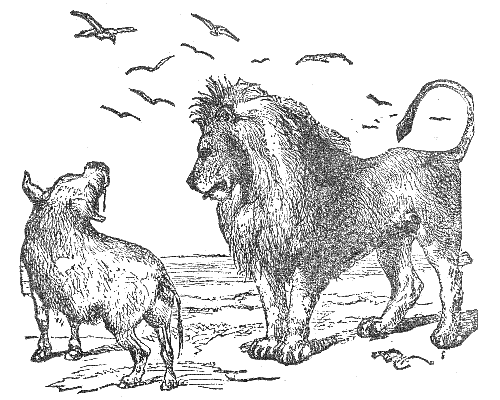

The Lion and the Wild Boar

(Perry 338; Chambry 203)

Λέων καὶ κάπρος

Ὅτι τὰς πονηρὰς ἔριδας καὶ τὰς φιλονεικίας καλὸν ἐστι διαλύειν, ἐπειδὴ πᾶσιν ἐπικίνδυνον τέλος ἄγουσιν.

ἐν ὥρᾳ, τὸ καῦμα δίψαν ἐμποιεῖ, εἰς μικρὰν πήγην λέων καὶ κάπρος ἦλθον πιεῖν. ἤριζον δὲ πρῶτος αὐτῶν πίῃ· ἐκ τούτου δὲ πρὸς φόνον ἀλλήλων . ἄφνω δὲ πρὸς , εἶδον γῦπας ἐκδεχομένους ὂς ἂν αὐτῶν πέσῃ, τοῦτον . διὰ τοῦτο λύσαντες τὴν ἔχθραν εἶπον “κρεῖσσόν ἐστιν ἡμᾶς φίλους γενέσθαι ἢ βρῶμα γυψὶ καὶ κόραξιν.”

The Lion and the Wild Boar

The following story shows that it is a fine thing to put an end to grievous quarrels and rivalries, when they are heading towards an end that imperils all.

At that time of summer, when the heat of the day causes thirst, a lion and a wild boar came to the same small spring to drink. They began to quarrel over which of them would drink first: from there, they grew frenzied to the point of killing one another. And when they stopped suddenly to catch their breath, they saw vultures waiting to devour whichever of them should fall. Wherefore, putting aside their enmity, they said “it is better that we be friends than food for vultures and crows.”

From: Fables

The fable (ainos, mythos, logos) as a form of Greek storytelling is at least as old as Hesiod (Op. 202-212; 8th C) and Archilochus (fr. 174; 7th C), and by the 5th century, we find references in Herodotus (2.134) and Aristophanes to Aesop as a writer of fables, i.e. a logopoios or a mythopoios. Much like the works of Homer, Aesop’s Fables were not at first written and compiled in an authoritative collection, but the name held some generic authority in 5th C Athens. Indeed, Aristophanes’ Birds contains the insult that an ignorant character has not “frequented Aesop” (“οὐδ᾽Αἴσωπον πεπάτηκας”, ll. 471-2). Still, we might more accurately speak of tales in the Aesopic tradition (attributed to Aesop) than of a work called Aesop’s. The tales themselves vary in length, but are generally short, contain personified animals, plants, objects, or gods, and end with a “moral” or lesson that is usually explicitly stated or reinforced. Various authors in antiquity produced their own “collections” of Aesop’s tales, in Latin and Greek, and in the middle ages, the Aesopic fable took on a new life and tradition. Collected here are Greek fables, in prose.

By: Aesop

( - -564)

Aesop, like Homer, was probably as mythical as his tales. Although he was widely known and celebrated in the ancient Greek world, his biography has many of the hallmarks of a pseudo-historical folk-hero. There is no agreement on where he was from, he was afflicted with one or more disabilities (e.g. he was mute, ugly and misshapen), and his death is said to have been tragic and noteworthy.

As a writer of fables, he was known already in the 5th C BCE by Herodotus, who believed him (“Αἰσώπου τοῦ λογοποιοῦ”) to have lived in the 6th C and been a slave to a Samian, Iadmon. The historian describes him as a fellow slave (σύνδουλος) of the Thracian Rhodopis, and so perhaps he meant to imply that Aesop, too, was from Thrace, an origin attested elsewhere (cf. Aristot. fr. 573 “ἦν δὲ Αἴσωπος Θρᾷξ”, Suidas Eugeion Samius DFGH 3 “Εὐγείτων δὲ Μεσημβριανὸν εἶπεν”; Αἴσωπος δὲ ὁ λογοποιὸς εὐδοκίμει τότε.; Heracleides DFGH 5 “Ἦν δὲ Θρᾷξ τὸ γένος.”). Still other sources claim he was a Phrygian or a Lydian. There exists an Imperial era biography, in Greek, in the form of a popular, fictionalized novel that consists largely of generic tales of a witty slave outfoxing his master, and then of a wise freedman spreading his wisdom in the form of stories as an advisor to Croesus, the Samians, the Babylonians, and the Egyptians. His death at Delphi at the hands of angry Delphians is well-known (Eusebius places it in 564 BCE; cf. a Greek inscription from 16 CE, found at Rome IG XIV 1297 col. II 15-18). Perry (1952, Aesopica) provides a handy collection of ancient testimonia.