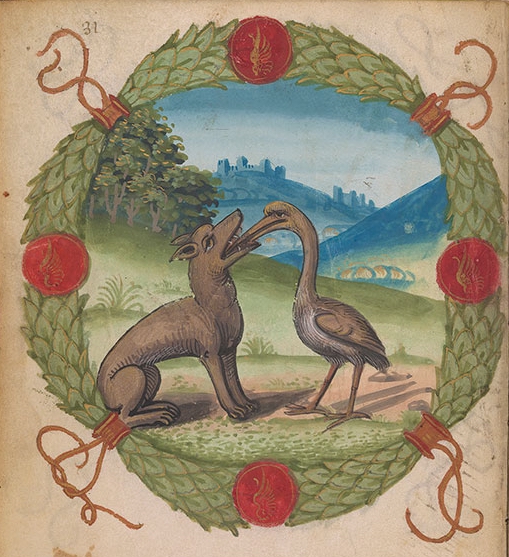

The Wolf and the Crane

(Phaed. 1.8)

Lupus et Gruis

Qui pretium meriti ab improbis ,

bis : primum quoniam indignos adiuvat,

impune abire deinde quia non potest.

Os devoratum cum haereret lupi,

magno dolore coepit

pretio ut illud extraherent malum.

tandem persuasa est ,

gulaeque credens colli longitudinem

periculosam fecit medicinam lupo.

pro quo cum pactum flagitaret praemium,

“Ingrata es” inquit “ore quae nostro caput

incolume et mercedem .”

The Wolf and the Crane

Whoever requests payment for a good deed from wicked men,

errs twice: first because he helps the unworthy,

and then because he is no longer able to walk away unpunished.

When a gulped-down bone stuck in the throat of a wolf,

overwhelmed by great pain, he began to entice one after another

with a reward to draw out the terrible thing.

At last a crane was convinced by an oath,

and, entrusting the length of her neck to his throat,

she wrought a perilous cure for the wolf.

When she demanded the agreed upon reward for this,

he said, “You are ungrateful, you who pulled your head

from our mouth unharmed and (now) demand a fee.”

From: The Aesopic Fables

Phaedri Augusti Liberti Fabularum Aesopiarum

Phaedrus' corpus of five books is the first known collection of fables in antiquity meant to be read and enjoyed on its own literary merit. Previously, such volumes were primarily reference books for rhetorical use (see the Aisopeia of Demetrius of Phaleron, 4th C BCE; cf. Αἰσωπείων ἀ, Diog. Laert. 5.80; Phaedrus himself presumably made use of one such book, if not that of Demetrius). This work, like that of Babrius, was written in verse, perhaps as a way to set it apart from earlier collections that were designed to be mined for material and influence, and the meters no doubt added respect and literary elevation that prose could not. In this way, fable went from material with which to make literature to literature itself. Fables had, naturally, appeared before in literature, especially in collections of verse, but primarily as a vehicle through which to make some greater point. The pure book of literary fables seems to have started with Phaedrus.

The first three books of his fables were written and published under Tiberius, the final two later, probably in the author's old age (cf. Phaed. 5.10.10). Stylistically, the poet was a fan of brevitas and colloquial speech. His poems are written in iambic senarii, the meter of Roman comedy. The fables irregularly make use of promythia (a sort of introductory, topical/categorical statement) and epimythia (gnomic statements that summarize the moral of a story). Over time, Phaedrus produced more “original” stories that lack an obvious Aesopic inspiration; topics are not only bestial, but historical, mythical, anecdotal, and generically droll.

By: Phaedrus

(-15 - 50)

Phaedrus—or perhaps Phaeder—is the first author we know to have produced a published collection of Aesopic fables meant to be read one after another, purely for literary enjoyment. Not much can be said with certainty about his life or person. A testimony in the principle manuscript reports that he was a freedman of Augustus; everything else we can hope to ascertain about Phaedrus and his life comes from his own work. He was Greek speaking and claimed a Greek literary heritage (Phaed. 3 prologue). If the prologue to his third book can be taken at face-value, he was “all but born in a school” near the Pierian Mount. He published his first book under Tiberius (Phaed. 2.5) and was not successful during his own lifetime. In his writings he complains of endless poverty and an icy reception in Roman literary circles (he is not mentioned in our extant authors until Marital, 3.20.5). He was indicted by Sejanus (Phaed. 3 prologue 40ff). We don't know the precise nature of this suit, but the outcome seems to have been against the poet. Despite persecution, the self-proclaimed unpopular pauper wrote into his old-age, producing five books of “fabulous” verse. He died most probably in the middle of the 1st C CE.