Babrius

At present, we cannot say with conviction precisely who Babrius was or where and when he lived. No ancient source mentions him, and he himself provides no biography. Even his name, reported variously in confused manuscripts as Babrius, Valerius Babrius, Babrius Valerius, and Valebrius, is reported without true surety. We can, however, offer compelling inferences from his extant work and what we know about ancient onomastics, literary culture, and linguistics.

The name itself, Babrius, is not Greek, but is well attested in Italy and Italian epigraphy. Furthermore, his verse bears several hallmarks of Latin choliambic metrics, especially that of Martial, and is full of patterns uncommonly found in Greek poesy. For these reasons, we can safely assume he was of Italian origin and a native speaker of Latin. It is more difficult to determine when he wrote, but the style and contents of his work, the metrical similarities to Martial, and the nature of the second book's dedicatee, point us towards the first or second century of our era. From the dedication, inscribed to the son of a king Alexander, and the references the poet made to Syria and the Syrian fabular tradition, it is likely that Babrius worked as a tutor in the court of a Hellenized king somewhere in Asia Minor. This king Alexander may have been a petty king, said by Josephus (AJ 18.140) to have been appointed by Vespasian, but on this no one can be certain.

In summary, therefore, one can be reasonably sure that Babrius was an Italian of the first or second century CE who lived and wrote in Roman Asia Minor.

A more complete—and very accessible—introduction to Babrius can be found in Perry's 1965 LCL edition: Babrius, Phaedrus. Fables. Translated by Ben Edwin Perry. Loeb Classical Library 436. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965, pp. xlviiff.

Works by this author

Aesopic Fables | Babrius

Μυθίαμβοι Αἰσώπειοι

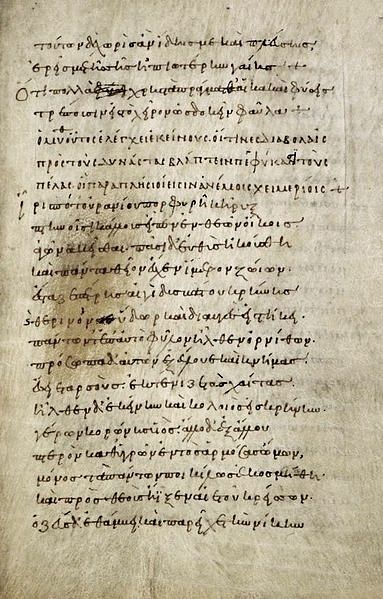

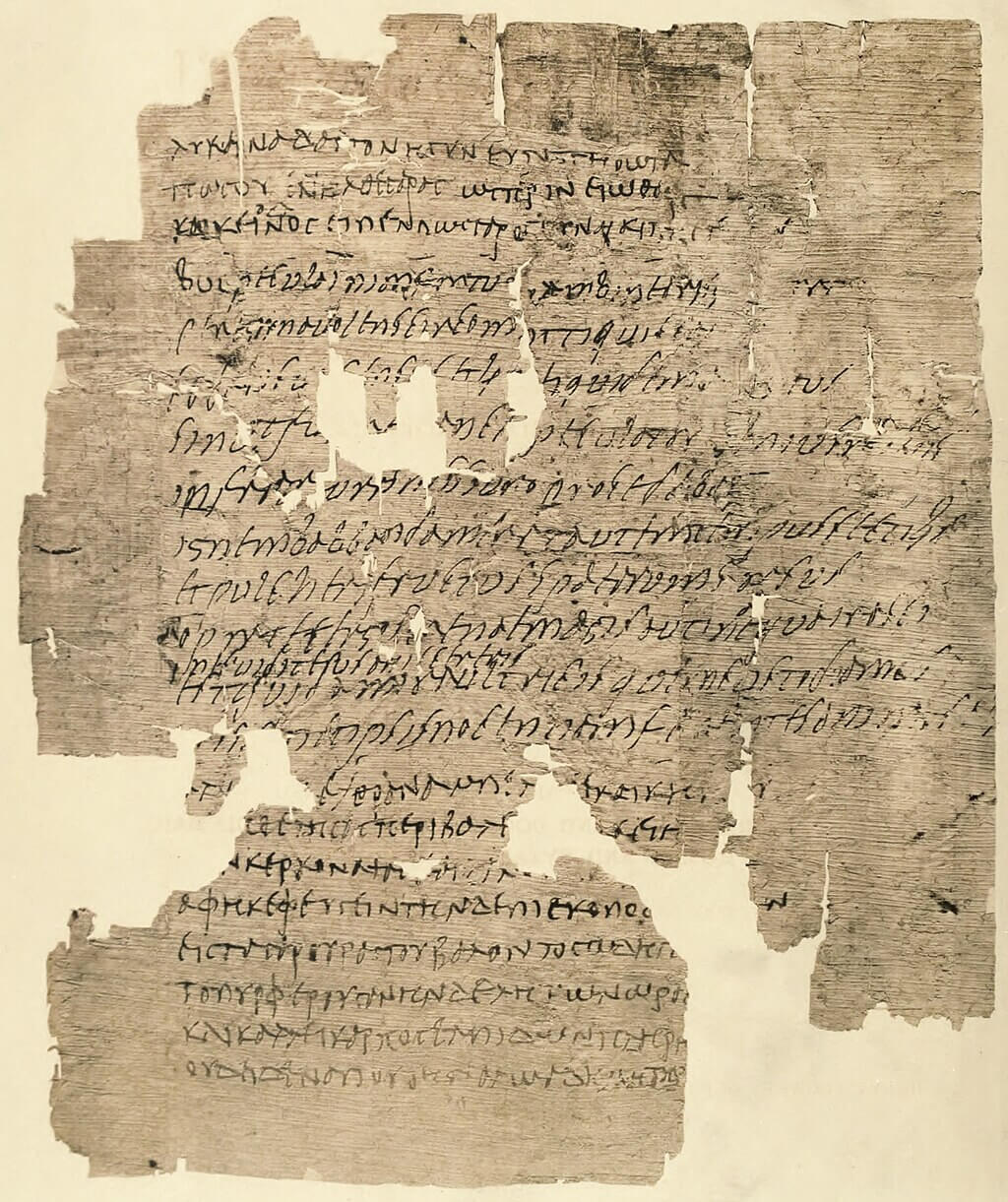

Babrius’ versified fables were originally published in two books (most likely; cf. Avianus’ preface) that contained roughly 200 poems. 143 survive in metrical form across five manuscripts, and a further 57 are known from prose adaptations and summaries. The first book addresses a—perhaps fictional—child named Branchos (“ὦ Βράγχε τέκνον”), presumably a pupil of Babrius, while the second book is dedicated to the son of a king Alexander (“ὦ παῖ βασιλέως Ἀλεξάνδρου”). While it is possible that these are one and the same individual, the two prefatory dedications differ in content noticeably, and the latter suggests that the second book was...