Aesopic Fables

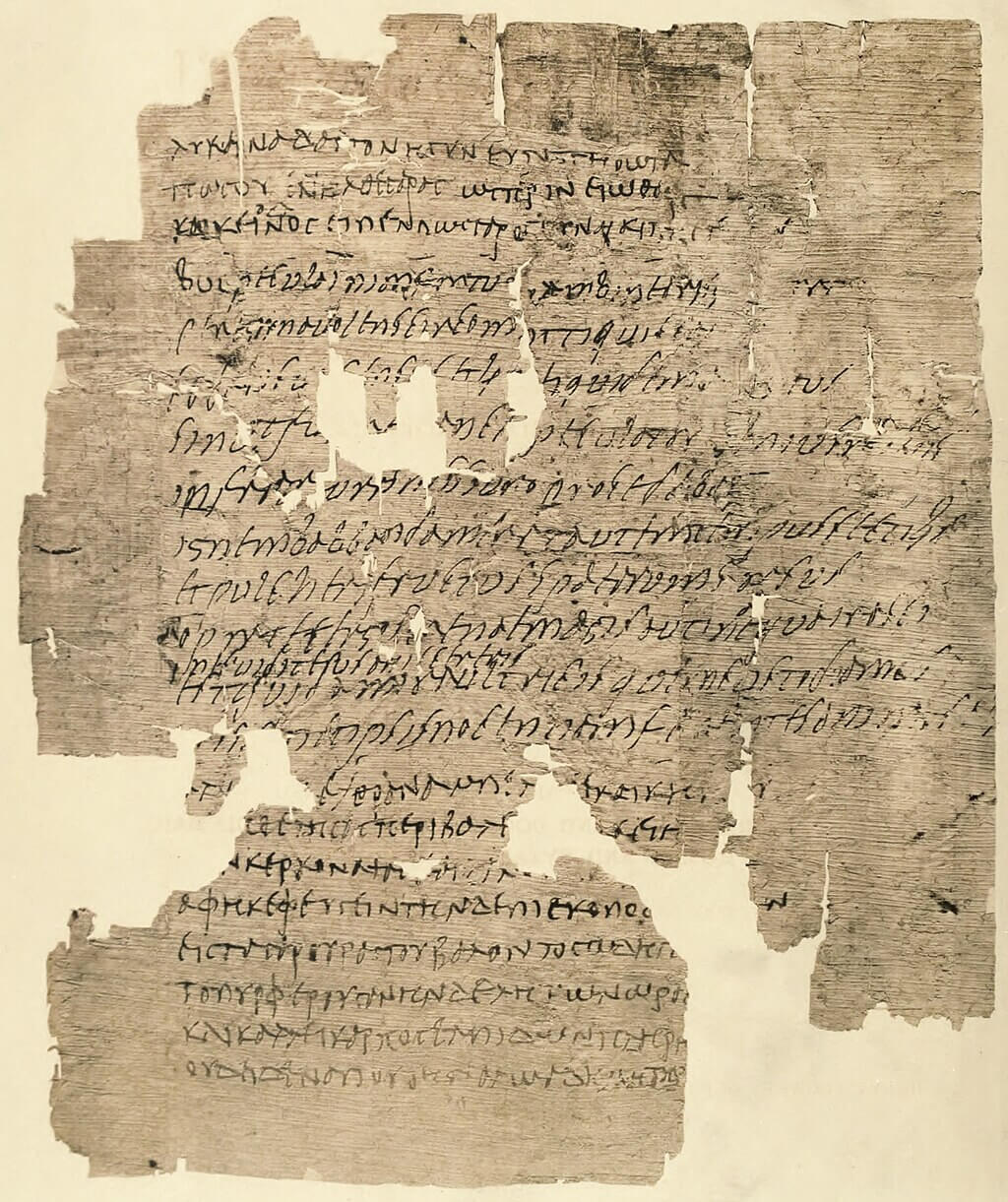

Babrius’ versified fables were originally published in two books (most likely; cf. Avianus’ preface) that contained roughly 200 poems. 143 survive in metrical form across five manuscripts, and a further 57 are known from prose adaptations and summaries. The first book addresses a—perhaps fictional—child named Branchos (“ὦ Βράγχε τέκνον”), presumably a pupil of Babrius, while the second book is dedicated to the son of a king Alexander (“ὦ παῖ βασιλέως Ἀλεξάνδρου”). While it is possible that these are one and the same individual, the two prefatory dedications differ in content noticeably, and the latter suggests that the second book was written some time after the first. For these reasons, it is generally assumed that the dedicatee of the second book was a young eastern princeling, whom Babrius sought to interest with a discourse on the eastern origin of fables, and not the pupil Branchos.

Our principle manuscript, codex Α (the Athoan manuscript), preserves 123 fables in alphabetical order, up to the letter Ο, where it abruptly ceases, mid-poem. Other manuscripts sourced via traditions of roughly equal antiquity also follow such an alphabetical arrangement, but do not contain the same sets of fables as codex Α, and they differ in order within each letter. There is, furthermore, no evidence that each book contained an entire set of fables from alpha to omega. Since it is likely that the second book, the preface of which starts with the word “Μῦθος” and is, thus, found under Μ, was published some time after the first, it makes more sense to attribute the alphabetical ordering of the fables to later editors and not to Babrius himself. For this reason, we cannot be certain to which book any particular poem originally belonged, and modern editions of Babrius are usually published as a single “book”.

Babrius’ fables vary in nature, structure, and likely source. Among his verses, the reader finds stories, epigrams, proverbs, and anecdotes. Epimythia are found inconsistently in the manuscripts; some poems have none and some are written in prose. This incongruity means that many, if not all, were probably added by later editors and scholars and not by Babrius himself. In addition to Greek sources in the Aesopic tradition, Babrius must have consulted some edition(s) of Assyrian fables, such as the Book of Achiqar, known to have been translated into Greek in antiquity and yet extant in Syriac. From this Syriac version, we can identify nine or ten Assyrian fables found in Babrius’ work.