Divided and Devoured

(Babrius 44)

Ἐνέμοντο ταῦροι τρεῖς ἀεὶ μετ᾿ ἀλλήλων.

λέων δὲ τούτους ,

ὁμοῦ μὲν αὐτοὺς οὐκ ,

λόγοις δ᾿ ὑπούλοις διαβολαῖς τε συγκρούων

ἐποίει, χωρίσας δ᾿ ἀπ᾿ ἀλλήλων

ἕκαστον αὐτῶν ῥᾳδίην θοίνην.

Ὅταν μάλιστα ζῆν θέλῃς ἀκινδύνως,

ἐχθροῖς , τοὺς φίλους δ᾿ ἀεὶ .

Divided and Devoured

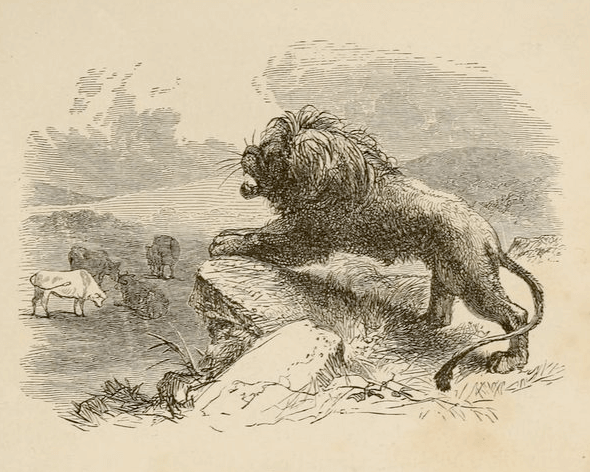

Three bulls always used to graze with one another.

A lion, watching for his chance to lay hold of them,

did not think he could defeat them together,

and so, stirring up discord with deceitful tales and false accusations,

he turned them into enemies, and by separating them from one another,

he had in each of them an easy meal.

Whenever you wish most of all to live free from danger,

do not trust in enemies, but watch over your friends always.

From: Aesopic Fables

Μυθίαμβοι Αἰσώπειοι

Babrius’ versified fables were originally published in two books (most likely; cf. Avianus’ preface) that contained roughly 200 poems. 143 survive in metrical form across five manuscripts, and a further 57 are known from prose adaptations and summaries. The first book addresses a—perhaps fictional—child named Branchos (“ὦ Βράγχε τέκνον”), presumably a pupil of Babrius, while the second book is dedicated to the son of a king Alexander (“ὦ παῖ βασιλέως Ἀλεξάνδρου”). While it is possible that these are one and the same individual, the two prefatory dedications differ in content noticeably, and the latter suggests that the second book was written some time after the first. For these reasons, it is generally assumed that the dedicatee of the second book was a young eastern princeling, whom Babrius sought to interest with a discourse on the eastern origin of fables, and not the pupil Branchos.

Our principle manuscript, codex Α (the Athoan manuscript), preserves 123 fables in alphabetical order, up to the letter Ο, where it abruptly ceases, mid-poem. Other manuscripts sourced via traditions of roughly equal antiquity also follow such an alphabetical arrangement, but do not contain the same sets of fables as codex Α, and they differ in order within each letter. There is, furthermore, no evidence that each book contained an entire set of fables from alpha to omega. Since it is likely that the second book, the preface of which starts with the word “Μῦθος” and is, thus, found under Μ, was published some time after the first, it makes more sense to attribute the alphabetical ordering of the fables to later editors and not to Babrius himself. For this reason, we cannot be certain to which book any particular poem originally belonged, and modern editions of Babrius are usually published as a single “book”.

Babrius’ fables vary in nature, structure, and likely source. Among his verses, the reader finds stories, epigrams, proverbs, and anecdotes. Epimythia are found inconsistently in the manuscripts; some poems have none and some are written in prose. This incongruity means that many, if not all, were probably added by later editors and scholars and not by Babrius himself. In addition to Greek sources in the Aesopic tradition, Babrius must have consulted some edition(s) of Assyrian fables, such as the Book of Achiqar, known to have been translated into Greek in antiquity and yet extant in Syriac. From this Syriac version, we can identify nine or ten Assyrian fables found in Babrius’ work.

By: Babrius

( - )

At present, we cannot say with conviction precisely who Babrius was or where and when he lived. No ancient source mentions him, and he himself provides no biography. Even his name, reported variously in confused manuscripts as Babrius, Valerius Babrius, Babrius Valerius, and Valebrius, is reported without true surety. We can, however, offer compelling inferences from his extant work and what we know about ancient onomastics, literary culture, and linguistics.

The name itself, Babrius, is not Greek, but is well attested in Italy and Italian epigraphy. Furthermore, his verse bears several hallmarks of Latin choliambic metrics, especially that of Martial, and is full of patterns uncommonly found in Greek poesy. For these reasons, we can safely assume he was of Italian origin and a native speaker of Latin. It is more difficult to determine when he wrote, but the style and contents of his work, the metrical similarities to Martial, and the nature of the second book's dedicatee, point us towards the first or second century of our era. From the dedication, inscribed to the son of a king Alexander, and the references the poet made to Syria and the Syrian fabular tradition, it is likely that Babrius worked as a tutor in the court of a Hellenized king somewhere in Asia Minor. This king Alexander may have been a petty king, said by Josephus (AJ 18.140) to have been appointed by Vespasian, but on this no one can be certain.

In summary, therefore, one can be reasonably sure that Babrius was an Italian of the first or second century CE who lived and wrote in Roman Asia Minor.

A more complete—and very accessible—introduction to Babrius can be found in Perry's 1965 LCL edition: Babrius, Phaedrus. Fables. Translated by Ben Edwin Perry. Loeb Classical Library 436. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965, pp. xlviiff.